Resorts World Sentosa (called RWS around here because Singaporeans love acronyms) with the larger island of Sinapore in the background. All images of RWS from Slate

's slideshow.

While the Passengers nervously watched USA and England keep alive their respective, overly optimistic quests for World Cup glory, Singapore welcomed the

opening of its second

den of iniquity integrated resort: Marina Bay Sands. Some work remains to be done on the structure, especially the much anticipated

Skypark atop the 55-story towers. But this post piggybacks on an

architectural write-up of the city-state's first integrated resort in

Slate: Resorts World Sentosa. The project

opened in time for the Chinese New Year in February and includes 1,740 hotel rooms spread over six locations, a maritime museum, convention and conference facilities, and loads of retail space, but these mostly serve as a fig leaf for the cash cow super casino.

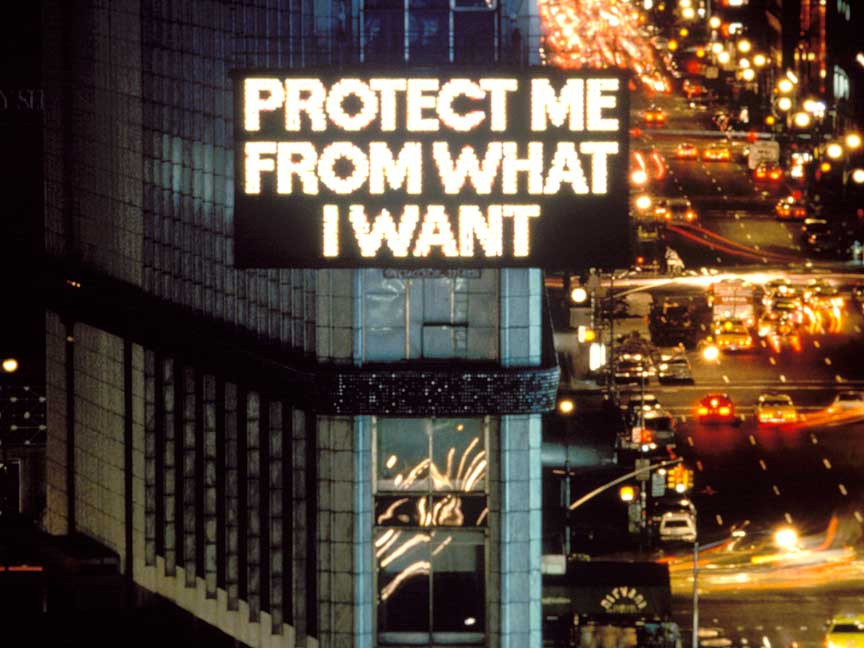

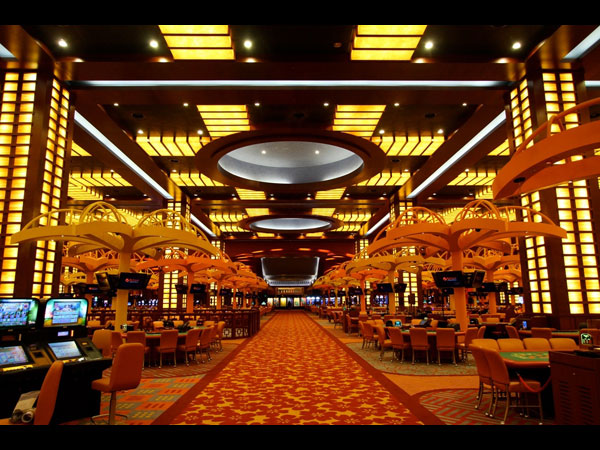

The gaming floor at RWS.

Traditionally the ruling

classes party of Singapore

have has looked down on gaming, but Macau is making money hand over fist from newly wealthy Chinese not allowed to gamble at home. So Singapore decided to patronize all the punters who might patronize a casino Only two casinos have been built and only as a part of larger euphemistically named integrated resorts. The first project was located on Sentosa a small island to the south, even easier to control and far from most Singaporeans . Sentosa visitors pay S$3 to set foot on the island, and Singapore citizens must pay a S$100 (about 72 USD) admission to lose money inside the casino. The gaming floor itself has been buried underground precisely to keep it away from public view. Families should concentrate their excitement on the brand-name excitement above ground, a shiny new

Universal Studios attraction. Those Singaporeans unable to control their losses can be added to a blacklist and refused entry to the casino.

Slate's architectural critic Witold Rybczynski has a fair amount of praise for the 121-acre project designed by postmodern pioneers

Michael Graves and Associates. The principal and his firm have carried out something of a

gesamtkunstwerk, an impressive total design effort extending from the hotel towers down to the flatware and the lamps in each hotel room. This seems well within the capabilities of a firm that

makes paper-towel holders for the discount retailer Target, but it hasn't been popular practice since the early twentieth century.

The high-end Cockfords hotel at RWS.

"Asians don't want to borrow from Western culture. They want their own architecture. Although they don't necessarily know what that is,"

says the condescending American Michael Graves. Rybczynsky claims the Cockfords hotel was designed without the flourishes of Classicism that punctuate much of the architect's work. This seems accurate if one ignores the green cupolas and refuses to see green rim encircling the top of the inhabitable floor as an overhanging cornice. The design does bother to subtract any capitals from the extended pilasters that emerge to support the ring of oversized pedestals. Also the name Cockfords does not necessarily suggest a Southeast Asian location.

Much of my hesitation to agree with Rybczynski stems from my dislike of the whimsical stunts that characterize Graves. His play with classical devices and bold colors seems increasingly naff and bears some responsibility for some of the

worst excesses of corporate architecture in the last thirty years. However, I concede that the design probably does match the brief set forth by the patrons. This was not the first resort executed by Graves; he did

Walt Disney World Swan, and his selection was probably a safe choice for Singapore. Indeed the firm specializes in architectural fantasies so it does not surprise that they built the blinders required to keep a supercasino super-clean.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)